“There is no denying the fact: the climate crisis is here, and it is real.”

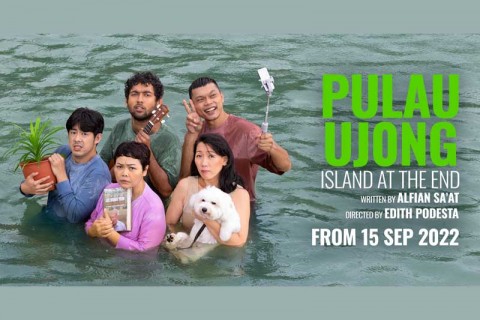

So opens Ivan Heng, the Founding Artistic Director of Wild Rice, when presenting the theatre’s newest play: Pulau Ujong / Island at the End. “What we choose to do, individually and collectively, could have more of an impact on the future than ever before.”

This statement captures the essence of Alfian Sa’at’s play very concisely. Not only is climate change very much imminent, but it’s also a complex issue that requires much more than individual action — it’s a global problem that needs a collective solution.

Central to conveying this idea is the structure of the play, set up as a series of interviews conducted with and speeches given by real people, reenacted on stage. It doesn’t sound very exciting, but it absolutely is; the sequence of the monologues and the resulting pacing of the play, engineered by Alfian Sa’at and brought to life by director Edith Podesta, evoke a sense of rising tension and urgency that keeps the audience enthralled throughout.

The speakers range from climate scientists, botanists and zoologists to environmental historians and activists, declaring their dreams for the future of Singapore’s environment and the world at large. They engage with climate change in different and occasionally questionable ways, showcasing a wide variety of opinions. This opens the audience’s eyes and ears to possible solutions to the climate crisis that they may not have considered or even encountered before, making it an effective format to deliver the play’s message.

The skilful acting and gorgeous costume design add another layer to this, making for such a striking performance that I came out of it reconsidering my dislike of monologues. Someone who stood out in particular is Al-Matin Yatim, who shows remarkable range by playing the Malayan tiger and one of the particularly aggressive crops with marvellous intensity, then his human acts with realistic restraint, slipping so wholeheartedly into each role that he seems to become a whole new actor with every appearance.

Besides the Malayan tiger and the energetic crops, other animals and plants take centre-stage during the play as well, alternating their stories with those of the human speakers. The actors make this a very enjoyable experience, the stories of polar bears, monkeys and trees tugging on heartstrings and making the audience audibly sniffle. It awakens a sense of care and responsibility in the spectators, with great potential to spring people into action.

On the flip side, these emotionally charged narratives also instil something else in the audience: feelings of both pity and guilt. The way these narratives are delivered contrasts rather strongly with the more composed human monologues. Where the zoologist speeches and activist interviews feel nuanced, the voices of the “natural world” take on a sharp edge that leaves no doubt: humans are a destructive force and the environment would be better off without us.

This is a rather strange choice considering the playwright’s aim — to dismantle the idea of “us” vs. “them” and show that humans are just as much a part of nature as every other creature. The central message of the play is muddled by the animals’ insistence that humans are essentially bad and that the world would be “heaven” without us in it.

Superimposing this radical voice on animals and plants not only simplifies their complex experiences, romanticising them to an extent, but also presents their narratives as objective reality, the indisputable feelings of the natural world. In contrast, human opinions remain just that — opinions, subjective and questionable. After each speaker leaves the stage, having shared their hopes and dreams for the future, our restored faith in humanity is shattered again by another story of despair and cruelty.

The playwright thus conveys the message that no matter how hard humans try to come up with a solution, we irreparably have a negative impact on the environment, and should interact with it as little as possible. This is a harmful conclusion to draw, potentially pushing people to think along ecofascist lines; it may not be the aim of the play to encourage this, but the more heart-wrenching monologues make it easy to slip into this interpretation.

Ultimately, what you take away from Pulau Ujong is up to you — its goal is to inspire, to diminish the gap between “us” and “them” and to encourage hope and action. It may not convey this message as strongly as it could, but its aim and its fantastic production make it an important, mesmerising and conversation-starting performance that’s absolutely worth seeing.

------

Show attended:

by Wild Rice

Date: 20 Sep 2022

Venue: Wild Rice @ Funan, Ngee Ann Kongsi Theatre

More about the show →

![[Review] A Pantun Response to #Huayi2018](/assets/Uploads/_resampled/FillWyI0ODAiLCIzMjAiXQ/i-came-at-last-to-the-sea-03.jpg) [Review] A Pantun Response to #Huayi2018

[Review] A Pantun Response to #Huayi2018

![[Review] Time Between Us – An Aftermath](/assets/Thumbs/_resampled/FillWyI0ODAiLCIzMjAiXQ/review-time-between-us-an-aftermath-1.jpg) [Review] Time Between Us – An Aftermath

[Review] Time Between Us – An Aftermath