“Paint ghosts over everything, the sadness of everything. We made ourselves cold. We made ourselves snow. We smuggled ourselves into ourselves. Haunted by each other’s knowledge. To hide somewhere is not surrender, it is trickery. All day the snow falls down, all night the snow. I try to guess your trajectory and end up telling my own story. We left footprints in the slush of ourselves, getting out of there.”

– Richard Siken, War of the Foxes

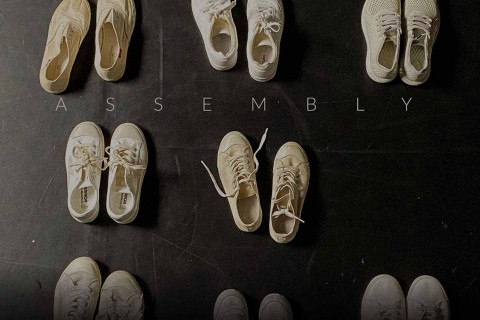

Directed by Han Xuemei and written by Adib Kosnan, Assembly, Drama Box’s latest theatrical experience, is a haunting one that invites audiences to roam into the spaces of a school compound, witnessing the struggles of, and journeying with, three students. Performed by Alvin Chiam, Auderia Tan, Nadya Zaheer and Timothy Wan, Assembly meticulously weaves intertwining stories of fear and psychological violence faced by these secondary school students amidst a backdrop of speculation and intrigue.

Due to the highly individually-experiential nature of this show, I decided to invite Arts Republic’s very own Max and Sam to share their experiences with me. They attended the show together during a public showing, and I attended Assembly separately on my own during a school showing.

Cheryl: Hello Max and Sam! I’m very excited to speak with you about Drama Box’s latest production – written by Adib Kosnan and directed by Han Xuemei – under Esplanade’s F.Y.I. Series, Assembly.

Presented as a production that deals with heavier themes like suicide, self-harm, bullying, and mental illness, the themes forefronting Assembly were some I found to be incredibly relevant to teens. The production’s take on violence, the cycles, and perpetuation thereof, struck a chord within me that I had not visited in a long time – and one that I had probably buried very deeply. Coming from a girls’ school myself (the same secondary school as the students I attended the production with that day, actually), my secondary school days were coloured with laughter, for the most part – until we lost a friend to suicide as well, and I understood that some coping mechanisms were actually forms of self-harm, and we gradually realised that the world was not as rosy as we had initially thought, growing up.

Secondary school for many, are crucial formative years, and for me these years of my life were some of the best of times, and the worst of times. Experiencing Assembly with (I nearly said “fellow”) secondary school students who now walk the very same school I used to attend plunged me back into those years, and I was suddenly a student again, hoping that the current students around me may never have to deal with the horrors present in the play, and yet knowing that at some point, we all end up having to. Life collects its dues and gives us a sobering reality in return.

Before we dive further in, I think we should start off by saying that I attended the show with secondary school kids during one of the showings reserved for students, and you two attended with the general public. I thought this was really interesting because my experience (and this show is so much of An Experience) was with the very audience demographic that Esplanade’s F.Y.I. is intended for.

Max: Yeah, thanks for bringing this up. I think it's really great that this work creates or exposes different perspectives of a topic or an incident. It then goes further to empower the audience/participants to take action — by moving their bodies to find the perspectives that they want.

I attended a show for the public. How did the students in the show you attended react to this experience? Were they active in attempting to follow the narratives? Did they feel lost?

Cheryl: Yes, there were points where there were several scenes going on simultaneously, so audience members were required to choose where they wanted to go and which scenes and conversations they wanted to watch. Most of the students I attended the show with were really excited about this, splitting up and then trying to recount what they heard to their friends who didn't get to see the scenes they did. Running around trading stories. I actually thought that was interesting especially given that this show tackled the spreading of rumours about a student and a teacher spending too much time together and how this was seen as an affair that was going on. The very nature of gossip and rumour-spreading means you can never get the full story, and that was exactly what was happening here.

Personally, only being able to see one scene at once while knowing in that moment that another scene was going on made me feel a very compelling sense of desperation. I wanted to split myself into two people, I wanted to see and hear everything. And that's what we as audience members usually expect when we come to watch shows – a full narrative laid out for us, where we entitle ourselves to a certain sense of vicariousness watching characters’ lives played out in front of us. The narratives in theatre that we are used to are neatly packaged. But that's where Assembly differs, and this experience of simultaneous narratives and needing to make a choice reminded me how limited we are – try as we might, in Assembly, and in life, we can never truly make ourselves privy to everything. We can never fully grasp the whole truth.

Sam: This is really very interesting, because this couldn't and didn't happen for the show we attended for the public! Although the audience showed equal excitement in running and chasing after the characters to the more hidden scenes away from the central classroom, there was no attempt to share what they witnessed with others. Even amongst the three of us, I didn't think about sharing what I saw on the other side of the set with Max or Phil (who was with us too) after we split up and got back together at several points.

For me, I thought about the unseen scenes that must have played out in reality in school (when I looked back at my own school-going experience) and reflected on how much I could have neglected my friends who could have been experiencing or coping with issues outside of classroom interactions: Did I miss out on something? Did I miss out on lending a listening ear or helping hand?

Cheryl: Absolutely. We're haunted by things we do not know, have failed to do, and even the things that we have done. Which aspects of the show stood out to you most in accentuating this?

Max: The notions of perspective and choice definitely stood out for me. But I'm also interested in how the team created the space that instilled a sense of ownership in the audience. There was a considerable amount of time between us entering the theatre and starting to see the drama take place. During this gap I just wandered around, trying to make sense of the space, recapping what our guide briefed us about, forming my own narratives in my brain. I feel this gap allowed me to attempt to 'own' the space, the story, and the issue. I then felt empowered to start making choices with my own assumptions. I was not told what to do, but I did what I felt I could do.

For quite some time, Drama Box has been putting audiences closer to stories or actions in the theatre. Sometimes, audiences become part of – or even make changes to – the shows. I've been learning a lot from these shows by observing various strategies to inspire active participation.

Sam: For me, it was less of perspectives, or I should say, I chose not to focus on the plurality of perspectives this time. We’ve been through a few other shows whose storylines branch into parallels, requiring audiences to ‘pick and choose’ the character or storyline to chase after, and in these shows, perspective was an obvious spotlight at play. I felt that Assembly is more than that. I am more drawn towards the diverse modes of participation that are made available this time round in Assembly, compared to the previous immersive experiential play (Flowers) we attended that was also directed by Xuemei. The many ways an audience member could participate in Assembly include choosing where to stand, what to gaze at, which surfaces to touch, whose feelings to empathise with, whose stage lines to hear. Even the sounds we make as an audience was a kind of participation into the story: the chatter and feet-shuffling of the audience mimicking a school ambience, furious writing on paper that was a timely match to the actor’s lines, the smell of Zebra markers. And in comparison to other immersive experiential plays that most likely carried a ‘whodunit’ element – where the plot pressurises and compels the audience to have to participate in other to solve the mystery or complete the story – Assembly had no mystery to be solved, and did not force the audience to have to complete a story. One could have watched Assembly passively from a bench if you were a tired soul; one could have watched Assembly by stubbornly following a single character from start till end; one could have watched Assembly by just lingering in the darkened spaces and not following anyone in the story at all; one could have watched Assembly reading all the reflection notes at the memorial spot. There was no one compulsory, better, or more efficient way to participate in an immersive or experiential show. I feel the creators of this show approached it with a lot of care and concern for the participating audience in mind, and were not simply engrossed or self-absorbed in wanting to force this story onto you.

Cheryl: I love that you brought up the immersive experiences of this production. Entering the darkened spaces of the Esplanade Annexe Theatre, Genevieve Peck’s lighting design subtly illuminated that ‘memorial spot’ Sam brought up, which was the first thing I noticed. The aspect of immersion happened immediately for me – Lee Yew Jin’s sounds of horror and haunting engulfed the performance space, and all at once the carefully curated space demanded a certain sense of respect from me, for the dead, for the living, and for whomever was left stranded in-between. Progressing through the play, the very versatile set designed by TK Hay, a four-sided structure (the very haunted Art Room) with folding walls on rollers and windows through which to view scenes that occurred within it, enhanced the sense of an audience watching the lives of these characters – a sense of viewership that while feeding my curiosity, made me rather uncomfortable because while this production invited audiences to be an active spectator of the harsh conversations and private moments experienced by these characters, it was still an invitation that a part of me felt it strange to so readily accept.

Max: Could you recall, at which point you felt you could 'do something'?

Sam: I did not feel there was such a point. I felt helpless as usual. However, there was an introspective change for me, I took the space and time to reflect on why I would not have had the courage to step forward to interrupt the bullying, or to lend a hand to any one of the characters if they had played out in real life. This experience was definitely less stressful than watching or participating in a forum theatre show.

Cheryl: Sam, I think it's interesting that you felt helpless and yet did not feel that there was a point where you could do something. Because helplessness does come from a place of wanting to do something, but also knowing that you cannot, or that you do not have the resources or opportunities to do so. Am I right in understanding that there inherently was a want to do something?

Sam: Yes, like your brain and heart could recognise there was some sort of social injustice and someone needs a kind of gentle company, but I didn’t, couldn't, or did not know how to, step up.

Cheryl: Yeah, definitely. I bring this up because I thought it crucial in theatrical experiences like these, where audiences are in some ways given more autonomy compared to sit-down-and-watch shows, and with this small gift of autonomy, whether intended by its gifters or not, arises possibilities of action that may not have been present if this was a conventional sit-down theatre show. In this case, I’m understanding that it was the seed of a possible action that was planted but that, some probably felt, would be fruitless to germinate.

Answering your question, Max: For this play, I did not feel it was my place to act, but to simply understand. Okay, maybe not simply, but desperately. I was desperate to understand. The small gift of audience autonomy imbued me with a determination of sorts, kind of like I was being sent on a quest to learn everything I could about these characters within the very short frame of time their lives were made privy to us – *laughs in jaded* as if knowing equals understanding, and understanding can save us all from ourselves. In an ideal world. Perhaps.

I felt like I was watching memories, or fragmented remnants of a forgotten past play out before my eyes. Perhaps it was the repetition of certain lines of dialogue that made me feel we were all stuck with these characters in a time loop – a very nice touch by playwright Adib Kosnan; perhaps it was because audiences watched scenes play out from within the large Art Room – a four-walled structure with windows through which to view the performance, and several openings on either end for doors – while we stood outside. In my mind, the characters whose small portions of lives were revealed to me were but echoes of a distant past, temporally removed from where I was. But even in this chasm there is, I think, a connection – through space and the sharing thereof. Towards the end of the play especially, all audiences were asked to stand in the Art Room instead of outside it. Standing in the very room where it happened, where so many events that were still not fully understood had unfolded, made me feel a connection to these characters. And perhaps that is my fascination with the aspect of horror in this show – these are ghosts of place. And though we think of ghosts as echoes of another time, sometimes a place holds so much memory within it that these ghosts can exist alongside us – perhaps not in a shared time, but through a shared place. Place is the bridge between two points of time on a timeline that propels its inhabitants forever forward.

In a similar vein, Assembly used horror as a vehicle upon which interlocking narratives of violence are conveyed. I especially loved that, and I think the best ones are those that capitalise on horror as a genre to flesh out inhumanity where we expect humanity. In Assembly, there was violence. Violence as a cycle; violence and the perpetuation thereof from an abused abuser to the abused. And what I loved was that this violence was shown as not only others-inflicted, but also self-inflicted. Rumours passed around and the fear they instil are forms of psychological violence that harms not only the abused but also, and in more subtle ways, the abuser. Self-harm is a form of violence towards the self; bullying, towards others; and the main bully was a girl who also struggled with bulimia which is again, violence inflicted upon the self. A bit of a tangent here, but this is also something I’ve thought about a lot, and something I cannot claim to have the answers for – but what drives a human being to inflict destruction or violence upon the self? How deep in the waters must one be then, when as humans our fundamental instinct is that of survival?

*proceeds to try to answer my own self-proclaimed unanswerable question lmao*

Personally I believe that in many cases, self-inflicted violence is a desperate attempt at containing violence within the self from not wanting to pass it on to others. Violence – psychological or physical, like fear (primarily psychological), is like a bloodied stream of water trickling down poisoning all in its wake, and unless work is done to acknowledge and confront it, it will, through experiences and the lingering remnants of its resulting trauma, continue to haunt its beholder, passed around like a plague. But even the plague-bearer must carry the cross of being haunted by both the sickness as well those they have poisoned.

The hardest part about all this for me was that though in an ideal world they should not have happened, where these instances of self-inflicted violence occurred, I could understand how and perhaps why they did. Often violence towards the self is a coping mechanism, albeit a destructive one – and destructive to varying degrees (which is something also seen in Assembly whose characters struggled with self-harm, bulimia, and suicide); and violence towards others, a reaching of a breaking point in which pain spills over and seeps through into our interactions with those around us. In an ideal world, these things should not have happened. But this world is not ideal, and they did. They do.

*End of discussion*

“Terror made me cruel…”

– Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights

In Assembly, there was not one singular ghost that haunted the school and its students. The hauntings experienced by both the play’s characters and the audience was not an external supernatural force or entity that we may come to expect, as told in the horror stories we are so familiar with. These are stories for a reason, and they remain just that – stories. Stories, like the ones we tell ourselves when unable to confront parts of our lives we regret, or have buried away – the roads not taken, the careless words uttered, the time of our lives wasted away. These are what haunts us. And so we weave tales to change our narratives, tales that turn into ghost stories of hauntings, because we can take refuge in attributing qualities of the supernatural to what we refuse to or cannot fathom and understand. But there is a reason most hauntings never happen just once – not when the teller is shackled to keep on telling them. These are stories we tell repeatedly to ourselves and to those who will watch and listen, whispered like a prayer that brings us to our knees, as if repetition solidifies and validates the versions of the narratives we long to be true.

But why do we tell stories? To make sense of a world that has spun out of our control, one that demands escape. But sometimes we flee the horrors of this world and its painful truths only to return to it again, bolting out of reality to come back to full circle, where it rears its ugly head and demands to be known and felt. Assembly reminds us, as we step out into reality, that the ghosts we encounter in our lives are often not supernatural in nature. There are many ways in which a haunting happens, and there are many stories that spin tales of a haunting that we can easily accept, but there is ultimately only one tale that we are most frightened to tell – the tale that shows us how what haunts us is ourselves.

------

Show attended:

by Drama Box

Date: 22 & 23 Jul 2022

Venue: Esplanade Annexe Studio

More about the show →

![[剧评] 人民公敌。现在进行式:超越经典意义的家乡剧场](/assets/Thumbs/_resampled/FillWyI0ODAiLCIzMjAiXQ/20150607-review-an-enemy-of-the-people-at-the-moment-tn.jpg) [剧评] 人民公敌。现在进行式:超越经典意义的家乡剧场

[剧评] 人民公敌。现在进行式:超越经典意义的家乡剧场

![[Review] Wonderland - An Afternoon Reverie](/assets/Thumbs/_resampled/FillWyI0ODAiLCIzMjAiXQ/11-20170616-review-wonderland-an-afternoon-reverie-tn.jpg) [Review] Wonderland - An Afternoon Reverie

[Review] Wonderland - An Afternoon Reverie