“What you allow is what will continue." This International Women’s Day, -wright Assembly teams up with artists of different disciplines to present Kotor, a response to Natalie Wang’s texts from her anthology The Woman Who Turned Into a Vending Machine.

Featuring sound and multimedia artist, Aqilah Misuary, the ensemble also features dance artists, Sufri Juwahir (Young Artist Award Recipient 2018) and Shaun Lim, alongside physical theatre practitioner, Kaykay Nizam. The team sees this response as an attempt to quash the perception that standing up for women’s rights is purely a woman’s responsibility.

Kotor (meaning “dirty” in Malay) explores how male movement artists, in their practice, could respond to issues surrounding sexual and physical abuse and gender bias. At the rehearsal, we caught performers Sufri, Shaun and Kaykay, and sound artist Aqilah, who is apparently the protagonist. As the male bodies move through the four stages from birth to life to a sense of helplessness, we read ritualistic displays of humanity, that sort of turned back the time to look at inherent primitive nature of man. The dancer’s confident strokes of extended arms and strong, grounded feet exudes vitality and energy, but also display a primal hunger or yearning for power. At this point in time, we are unsure if the male bodies are embodying, embracing or empathising the female perspective because we are missing a vital piece of the puzzle — visual projections. Nevertheless, the male figures soften in the last segment of the performance upon receiving knowledge in the form of paper and texts, and interactions with the female character. They become connected, holding on to the same lifeline that seems to trace its source back to the female body, seemingly retracing the steps of a female homemaker, experiencing a kind of helplessness. Whether it is the helplessness of a male body not knowing how to respond to someone else reaching out or a re-enactment of a female’s helplessness, we have to wait and see the final production.

We speak to Creative Producer Farhanah Diyanah (FD) and Choreographer Ismail Jemaah (IJ) to find out more about the creative processes behind the scenes.

1. How can movements respond to issues surrounding sexual and physical abuse and gender bias?

IJ: When I think of movement I kinda relate it to two things — one is the idea of body language, something which is usually a subconscious act, and at other times, intentional, to emphasise the message a person is communicating; another is more like intentional movement patterns like those found in dance, or gestures rooted in a certain culture or society. We see these gestures and body language and infer information from that. I feel movement helps translate what we feel, that are difficult to say, across to each other.

FD: As a writer, I’m more familiar with expressing these through words, but after being involved in a couple of dance productions (as production manager, stage manager and a dramaturg) I see that the body can really be a powerful tool to express something without having to verbalise it with words. However, the intentions and objectives of the choreographer or in Kotor’s case, the creative team, has to be clear so that what needs to be expressed via the body can be articulated during rehearsals and in the show. We need to be able to allow the audience to relate what they are seeing to their daily experiences so that they can make meaning of what they are seeing.

2. Farhanah mentions the need for a more proactive approach to deal with issues through art. What does it mean by "proactive approach"?

IJ: Maybe in terms of process, we first look into ourselves and our dealings with people around us. Second, we look into situations beyond our reach and how we can address these issues within our own circles. Third, the work presents itself as an opportunity to reach out to the audience, allowing the work to become a medium to trigger discussions and thoughts about these issues.

FD: Kotor is our effort as artists in taking action by hoping to effect change, instead of waiting for changes to happen to an issue or a situation.

3. How does the creative team think that art can help audience reflect on their own consciousness when faced with such issues?

IJ: Art makes u feel something intangible, and with that it brings to light those hidden thoughts and feelings, bring them up to the surface to be attended to.

FD: For me, it’s all about the intentions first. Because as creators we need to know why we are investing our time, critical thinking and emotions in a project, why it is important and why it is relevant. And then together, we ensure that the execution carry those intentions and objectives along. Whether or not the audience reflects, it is something beyond our control, but we hope they do.

4. When creating the piece, did the team map out a kind of storyline in their head before they produce the movements? Or is it created based on the emotions they feel in response to a certain issue identified as the core in the texts?

IJ: I feel we started by working with a skeleton of a narrative, and then we fill in the skeleton with what we feel and experience as we go along.

FD: Ismail suggested to tell this piece using the stages of life: birth, teenage, adulthood and old age. Through the texts in The Woman Who Turned Into the Vending Machine by Natalie Wang, I managed to pick out the texts that fit this life cycle and situations characters may face during these different stages. Then we sat down and talked about what the themes are in these texts, what the issues are currently happening in our society. And he created the choreography from there.

------

Kotor

by -wright Assembly

Date: 7 - 10 Mar 2016

Venue: Rumah P7:1SMA, Stamford Arts Centre #03-01, 155 Waterloo St, Singapore 187962

Visit event page

关于数字、剧场与爪吗的二三事

关于数字、剧场与爪吗的二三事

Reflecting on Life – Timothy Wan opens up about post-life choices

Reflecting on Life – Timothy Wan opens up about post-life choices

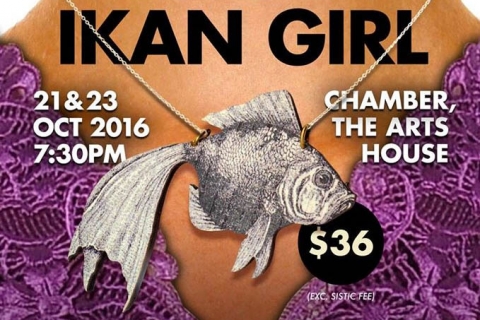

Of Myths and Legends – At the Rehearsal of Ikan Girl

Of Myths and Legends – At the Rehearsal of Ikan Girl