Oliver Chong is a humane director who is pretty soft-spoken (contrary to my imaginary impression projected on him). He sports a faint smile on his lips every time we arrive at a comical scene even though he must have watched it a hundred times over. Sitting diagonally across us, Oliver looks like he really enjoys watching his cast do their thing. He laughs louder than he critiques; he looks more excited and amused with every experiment his actors trial. He rarely pauses the rehearsal. Usually, his feedback is accumulated and communicated to the actors at the end of each session or the rehearsal block. Not sure if this is because of the amount of trust he has for this team, due to their long-time camaraderie, or because they’ve been through many improvs for the script during their pre-rehearsal workshops.

Everyone looks comfortable in their own skins as they continue to try things out and make progress with each scene.

Oliver also has a thing about space and the architecture of space. Both times we attended his rehearsals (The Spirits Play last year) for the first time, he will conscientiously take us through the imaginary setup for the stage in the rehearsal space. Also, using the handcrafted model of the stage he envisions, we get the big picture of how wide or deep the stage will be, the dimensions of the furniture or centrepiece, and the mathematics behind the angle of elevation from the perspective of the audience.

As a mathematician, I pretty much enjoy learning about these workings behind a stage that props up the entire play. It is not just about the emotional and qualitative aspects of a theatre, but also about the quantifiable, perhaps dry, technical aspects of theatre. It gives one a great sense of faith and security, knowing that the director puts in a lot of consideration into the field perspective of the audience.

It is pretty impossible to talk about the rehearsal without giving away the show although we expect the show to turn out very differently from what we’ve seen in 126 Cairnhill Arts Centre. First off, we haven’t seen the lighting or sound design. But it is a pleasure to simply focus on listening to the experienced actors say their lines while taking up several roles as demanded by the script. The juxtaposition of the realms unfolds clearly even in the absence of lights and sound design, or finished props.

Several plots/dimensions/worlds overlap in this play, penned collaboratively by Oliver and Liu Xiaoyi. It is said that the play is inspired by 聊斋志异 (Liao Zhai Zhi Yi: Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio). I think more accurately, the writers are inspired by the power play between spirits, beasts and Man: their manipulation of each other, debts of gratitude and inevitably, the insatiable desire for lust and greed.

They are struck by the observations noted by the author of Liao Zhai, Pu Song Ling (蒲松齡), in his strange tales — More often than not, the spirits and beasts in the stories harm others in self-defence or for revenge, whereas Man can resort to murder because of greed. The play also tries to parallel Pu’s unflinching confrontation of Man’s desire for lust.

Oliver also mentions that one of the motivations to write this plot has to do with the pending expiration of the first 60-year lease of landed property in Singapore along Geylang Lorong 3. So, in the play, we are looking at characters dwelling in an old apartment seemingly locked in time. The set looks as if time hasn’t passed for the protagonist Mr Pu for the last few decades. Either that, or he is just nostalgic for old times’ sake, isolated from the rest of the world.

Audience can expect a dream within a dream, humans and others, corruption, a civil servant and a futile writer, gender power play, and a profanity-cursing rod puppet dog bespoke-d by Oliver himself.

During a short reading of the play at Grassroots Bookroom, director Oliver Chong answers a question on why multiple accents are used in the play. In response, both Oliver and Xiaoyi elaborate that they are interested in the expanded possibilities of space once you cross a classic script with the modern world, specifically one in Singapore's context. Also, the multiplicity of languages and nationalities opens up a larger space of cultural context to play within, along with the potential to explore the interaction between the ‘locals’ and the ‘aliens’.

We’ll have to watch the play to find out if “Liao Zhai” in Citizen Dog is just a publicity gimmick or a discourse on humanity.

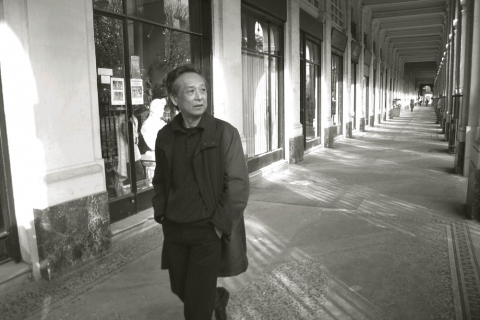

与高行健谈文化、美学、亚洲与新加坡

与高行健谈文化、美学、亚洲与新加坡

Interview with Andrew Sutherland - Erasing the line between climate change and social issues

Interview with Andrew Sutherland - Erasing the line between climate change and social issues

关于数字、剧场与爪吗的二三事

关于数字、剧场与爪吗的二三事